Keep your foot in it, and the Spitfire just keeps gathering speed-it'll cruise at 70 mph without strain.

gasoline, a quarter-tank (10

quarts) allows you about three days to find a gas station.

The

thrifty will love the Triumph's ability to wring miles out of a gallon

even when driven fast. But only an oriental mystic in the bed-of-nails

tradition will enjoy the things the car does to one's legs. Assume the

position behind the wheel and you will immediately notice a couple of

things. First, it will come to you that having one's left leg stretched

out into nothingness, and the right leg crooked well back, is

uncomfortable. This is mostly un- avoidable, as the clutch, brake and

accelerator pedals are quite closely situated, while the toe-board is up

there by the wheel-well. Moving the entire control- pedal group forward,

and adding a rest, or "dead-pedal" for one's left foot would

make the driver much more comfortable. The second revelation comes after

you have been driving for a time. Then, you become aware that your right

shin, which falls naturally against a structural member bracing the cowl,

is beginning to ache.

Our

Spitfire had all of the posh extras, including a good AM-FM radio. Often,

a good radio is wasted in a sports car, be- cause there is so much noise

you can't hear it anyway. It is worth having in the Spit- fire; the car is

fairly quiet by overall small- car standards, and really exceptional for a

small sports car. Engine noise is very muted, and the raucous blat from

the exhaust we once considered a sine qua non for Triumphs has been

subdued to a nice, mellow hummmm. Even wind noise is largely

absent. The top doesn't flap or drum, and you can run along at speed with

both windows cranked down without get- ting a lot of buffeting.

Such

noise as is there all seems to come from the drive train, and in the form

of road-rumble. There is a bit of transmission whine, and a kind of

muffled grumbling from the prop shaft and final drive. Not the worrisome

type noise; just an aware- ness that things are whirling and churning

earnestly.

Handling

and general road behavior is a mixture of good and bad. On the good side,

we must say that the car feels well balanced. Swing-axle rear suspensions,

like that on the Spitfire, tend to produce over- steer. Nose-heavy weight

distribution tends to produce understeer. The Spitfire carries 57.7% of

its 1680 lbs. in the front, and that forward weight bias seems to exactly

cancel whatever oversteering tendencies the rear suspension might lend.

On the beneficial side, too, is the car's low center of gravity. We don't know what

this

would be in inches, but it is obviously very low-because that is how the

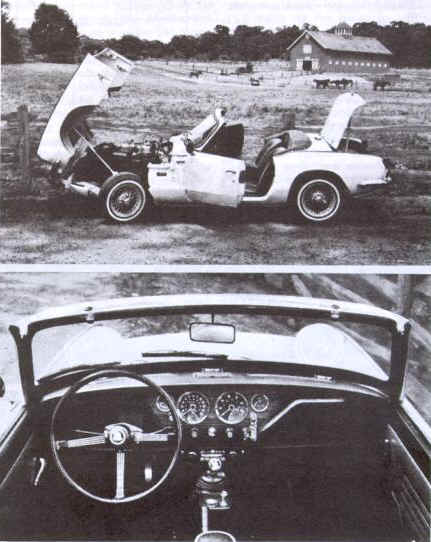

car is built. Triumph uses a backbone frame under the Spitfire, and the

frame structure dodges around to allow people and major components close

proximity with the road surface. Even with the narrow track (49 inches in

front, 48 inches at the rear) the Spitfire stands securely planted on the

road.

All sports cars have quick steering-it is an article of faith-and the Spitfire's steering is as quick as most. But it doesn't really feel that way. In fact, it feels a trifle heavy and lifeless. We decided after some reflection on the matter that it feels as though there is not enough caster at the front wheels and too much friction in the

steering. So the car feels dull

and unresponsive at low speed; becoming dull and twitchy when you get

motoring along rapidly. The steering friction may have been peculiar to

our particular car, or might disappear with more breaking-in. Caster is

built in at the factory and any sweeping corrections would have to be made

there.

One of the reasons for buying a Mk. III anything is to be one-up on those who have the Mk. 11 version of whatever it is. Thus, nothing is more irritating than having a Mk. III that looks exactly like a Mk. 11 or maybe only a Mk. 11-and-a-half. You can relax. The Spitfire Mk. III has external,